Jassy–Kishinev Offensive (August 1944)

- "Jassy–Kishinev Offensive" redirects here. For the earlier operation, see First Jassy-Kishinev Offensive.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

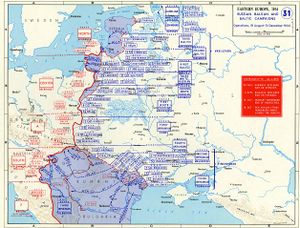

The Jassy-Kishinev Operation or Iaşi-Chişinău Operation[1][7][8][9] (Russian: Ясско-кишинёвская стратегическая наступательная операция, translation: Jassy-Kishinev Strategic Offensive Operation),[10] named after the two major cities (Iaşi and Chişinău) that define its staging area, was a Soviet offensive against Axis forces, which took place in Eastern Romania during 20–29 August 1944. The 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts of the Red Army engaged Army Group South Ukraine, which consisted of combined German and Romanian formations, in an operation to reclaim the Moldavian SSR and destroy the Axis forces in the region, opening a way into Romania and the Balkans.

The offensive resulted in the encirclement and complete decimation of defending German forces, allowing the Soviet Army to resume its strategic advance further into Eastern Europe. It also forced Romania to switch allegiance from the Axis powers to the Soviet Union.

Contents |

Setting the stage

The Red Army had made an unsuccessful attack in the same sector, known as the First Jassy-Kishinev Offensive from 8 April to 6 June 1944. During 1944, the Wehrmacht was pressed back along its entire front line in the East. By May 1944, the South Ukraine Army Group (Heeresgruppe Südukraine) was pushed back towards the prewar Romanian frontier, and managed to establish a line on the Dniester river, which was however breached in two places by Red Army bridgeheads. After June, calm returned to the sector, allowing the rebuilding of the German formations.

While up to June 1944 Heeresgruppe Südukraine was one of the most powerful German formations in terms of armour, it had been denuded during the summer, with most of its armoured formations moved to the Northern and Central front, in order to stem Red Army advances in the Baltic states, Belarussia, Northern Ukraine, and Poland. On the eve of the offensive, the only armoured formations left were the 1st Romanian Armoured Division, and German 13th Panzer and 10th Panzergrenadier Divisions.

Failure of intelligence

Soviet deception operations prior to the attack worked well. The German command staff believed that the movement of Soviet forces along the front line was a result of a troop transfer to the north. Exact positions of Soviet formations were also not known until the final hours before the operation.[11]

Soviet strategy

Stavka's plan for the operation was based on a double envelopment of German and Romanian armies by 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts.[1][12]

2nd Ukrainian Front was to break through north of Iaşi, and then commit mobile formations to seize the Prut River crossings before the withdrawing German formations of 6th Army could make it there. It was then to introduce 6th Tank Army into the battlefield to seize the Siret River crossings and the Focşani Gap, a fortified line between the Siret River and the Danube.

3rd Ukrainian Front was to attack out of its bridgehead across the Dniester near Tiraspol, and then insert mobile formations with a mission to head north and meet the mobile formations of 2nd Ukrainian Front. This would lead to the encirclement of the German forces near Chişinău.

Following the successful encirclement, 6th Tank Army and 4th Guards Mechanized Corps were to be launched towards Bucharest and the Ploieşti oil fields.

Progress of the offensive

General

Both the 2nd and the 3rd Ukrainian Front undertook a major effort, leading to a double envelopment of the German Sixth Army (2nd formation) and parts of the Eighth Army. The German–Romanian front line collapsed within two days of the start of the offensive, and 6th Guards Mechanized Corps was inserted as the main mobile group of the offensive. The initial break-in in the 6th Army's sector was 40 km deep, and destroyed rear-area supply installations by the evening of August 21. By August 23, the 13th Panzer Division had dissolved as a coherent fighting force, and the German 6th Army had been encircled to a depth of 100 km. The Red Army mobile group managed to cut off the retreat of the German formations into Hungary. Isolated pockets of German formations were trying to fight their way through, but only small remnants managed to escape the encirclement.

Detailed study of the Soviet breakthrough

Operations of 3rd Ukrainian Front (Commander Army General Fyodor Tolbukhin)

The main effort of the front was in the sector of the 37th Army (2nd formation) (Commander Lieutenant General Sharokhin). The main effort of the 37th Army was with 66th Rifle Corps and 6th Guards Rifle Corps. The 37th Army had a 4 km wide breakthrough frontage assigned to it. It was divided in two groupings, two Corps in the first echelon, and one Corps reserve. According to the plan, it was to break through the depth of the German–Romanian defense lines in 7 days, to a distance of 110–120 km, with a goal to cover 15 km per day during the first four days.

66th Rifle Corps (Commanded by Major General Kupriyanov), consisted of two groupings (61st Guards Rifle and 333rd Rifle Divisions in the first echelon, and 244th Rifle Division in reserve). Attached were 46th Gun Artillery Brigade, 152nd Howitzer Artillery Regiment, 184th and 1245th Tank Destroyer Regiment, 10th Mortar Regiment, 26th Light Artillery Brigade, 87th Recoilless Mortar Regiment, 92nd and 52nd Tank Regiment, 398th Assault Gun Regiment, two Pioneer Assault Battalions, and two Light Flamethrower Companies.

Corps frontage 4 km

Corps breakthrough frontage 3.5 km (61st Rifle Division 1.5 km, 333rd Rifle Division2km)

Troop density per kilometer of frontage:

- Rifle battalions 7.7

- Guns/mortars 248

- Tanks and assault guns 18

Superiority

- Infantry 1:3

- Artillery 1:7

- Tanks and assault guns 1:11.2

There is no manpower information on the divisions, but they probably had between 7,000-7,500 men each, with 61st Guards Rifle Division perhaps at 8,000-9,000. The soldiers were prepared over the course of August by exercising in areas similar to those they had to attack, with emphasis on special tactics needed to overcome the enemy in their sector.

Troops density in 61st Guards Rifle Division sector per kilometer of frontage was:

- Rifle battalions 6.0

- Guns/mortars 234

- Tanks and assault guns 18

Troops density in 333rd Rifle Division sector per kilometer of frontage was:

- Rifle battalions 4.5

- Guns/mortars 231

- Tanks and assault guns 18

Initial attack

333rd Rifle Division did not establish a reserve and put three regiments in the first echelon. The 61st Guards Rifle Division attacked in a standard formation of two regiment in the first echelon and one in reserve. This proved to be fortunate, because the right wing of the 188th Guards(?) Rifle Regiment was unable to advance past the Plopschtubej strongpoint . 189th Guards Rifle Regiment on the left wing made good progress though, as did 333rd Rifle Division on its left. The commander of 61st Guards Rifle Division therefore inserted his reserve (187th Guards Rifle Regiment) behind 189th Guards Rifle Regiment to exploit the break-in. When darkness came, 244th Rifle Division was inserted to break through the second line of defense. It lost its way though, and only arrived at 23:00, by which time elements of 13th Panzer Division were counterattacking.

The German–Romanian opposition was XXX. and XXIX. AK, with 15th, 306th German ID, 4th Romanian Mountain Division, and 21st Romanian ID. The 13th Panzer Division (Wehrmacht) was in reserve. At the end of day one, 4th Romanian Mountain (General de divizie (Major General) Gheorghe Manoiliu), and 21st Romanian Divisions were almost completely destroyed, while German 15. and 306. Infanteriedivision were heavily damaged (according to a German source: 306. ID lost 50% in the barrage, and was destroyed apart from local strongpoints by evening). Almost no artillery survived the fire preparation.

The 13th Panzerdivision counter-attacked the 66th Rifle Corps on the first day, and tried to stop its progress the next day, but to no avail. A study on the division's history says 'The Russians dictated the course of events.' 13th Panzerdivision at the time was a materially understrength, but high manpower unit, with a high proportion of recent reinforcements. It only had Panzer IVs, Sturmgeschütze III and self-propelled anti-tank guns. At the end of the second day the division was incapable of attack or meaningful resistance.

At the end of the second day, the 3rd Ukrainian Front stood deep in the rear of the German 6th Army. No more organised re-supply of forces would be forthcoming, and the 6th Army was doomed to be encircled and destroyed again. Franz-Josef Strauss, who was to become a very important German politician after the war, served with the Panzerregiment of the 13th Panzer Division. He comments that the division had ceased to exist as a tactical unit on the third day of the Soviet Offensive: 'The enemy was everywhere.'

The comment on the result of 66th Rifle Corps operations in Mazulenko is that "Because of the reinforcement of the Corps and the deep battle arrangements of troops and units the enemy defenses were broken through at high speed."

Comments by German survivors on the initial attack were that "By the end of the barrage, Russian tanks were deep into our position." (Hoffmann). A German battalion commander (Hauptmann Hans Diebisch, Commander II./IR579, 306.ID) commented that "The fire assets of the German defense were literally destroyed by the Soviet fighter bombers attacking the main line of resistance and the rear positions. When the Russian infantry suddenly appeared inside the positions of the battalion and it tried to retreat, the Russian air force made this impossible. The battalion was dispersed and partly destroyed by air attacks and mortar and machine gun fire."

Alleged Romanian collapse

It is often alleged that the speed and totality of the German collapse were caused by Romanian betrayal. For example, Heinz Guderian wrote of Romanian betrayal in his book Panzer Leader. The study of the combat operations by Mazulenko indicates that this is probably not correct. Romanian formations did resist the Soviet attack in many cases, but were ill-equipped to defend themselves effectively against a modern army, due to a lack of modern anti-tank, artillery, and anti-air weapons. In contrast to German claims, for instance, in the symposium notes published by David Glantz, or in the history of the Offensive published by Kissel, it appears that Romanian 1st Armoured Division did offer resistance against the Soviet breakthrough, but was quickly defeated.[13]

The surrender of Romania took place at a time when the Soviet Army already stood deep inside Romania, and the German 6th Army had been cut off from the rest of the Wehrmacht troops in Romania. The opening of hostilities between the Wehrmacht and the Romanian Army commenced after a failed Coup d'état by the German ambassador.

German-Romanian combat

Concurrently, a coup d'état led by King Michael of Romania on 23 August deposed the Romanian leader Ion Antonescu. The Wehrmacht concentrated most of its forces in Moldavia, leaving only 11,000 troops deployed in the vicinity of Bucharest, with another 25,000 around the Ploieşti oilfields. German military formations promptly attempted to seize Bucharest in order to suppress the coup the following day, but were repelled by Romanian troops, who had some air support from the United States Air Force. German forces moving in to reinforce the assault on Bucharest from the west bank of Prut were cut off and destroyed by the rapidly advancing Soviet Army. At the same time, Wehrmacht formations guarding the Ploieşti oil fields were attacked by Romanian troops, and attempted to withdraw to Hungary, again suffering heavy losses in the process. During the fighting, the Romanian Army captured 50,000 German prisoners, who were later surrendered to the Soviet Army.[14]

Romanian sources claim that internal factors played a decisive role in Romania's liberation from the Nazis, while external factors only gave support; this version is markedly different from the Soviet position on the events, which holds that the Offensive resulted in the Romanian coup and liberated Romania with the help of local insurgents.[12][15]

Consequences

The German formations suffered very high irrecoverable losses of about 200,000 men, while Soviet losses were extremely low for an operation of this size. The Red Army advanced into Yugoslavia and forced the rapid withdrawal of the German Army Groups E and F in Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia to rescue them from being cut off. Together with Yugoslav partisans and Bulgaria they liberated the capital city of Belgrade in 20 October.

On the political level, the Soviet Offensive on the Yassy-Kishinev line triggered King Michael's coup d'état in Romania, and the switch of Romania from the Axis to the Allies. Almost immediately, a small border war between Romania and Germany's forced ally Hungary erupted over territory that Romania was forced to cede to Hungary in 1940, as a result of the Second Vienna Award.[16]

Following the success of the operation, Soviet control over Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, which had been occupied by the USSR in 1940, was re-established. Soviet forces proceeded to collect and expel the remaining Romanian troops. According to Anatol Petrencu, President of the Historians' Association of Moldova, over 170,000 Romanian soldiers were deported, 40,000 of which were incarcerated in a prisoner-of-war camp at Bălţi, where they died of hunger, cold, disease, or were executed.[17]

Formations and units involved

Soviet

- 2nd Ukrainian Front - Army General Rodion Malinovsky

- 6th Guards Tank Army - Major General A.G. Kravchenko

- 18th Tank Corps - Major General V.I. Polozkov

- Cavalry-Mechanized Group Gorshkov - Major General S.I. Gorshkov

- 5th Guards Cavalry Corps

- 23rd Tank Corps - Lieutenant General A.O. Akhmanov

- 4th Guards Army - Galanin

- 27th Army - Lieutenant General S.G. Trofimenko

- 52nd Army - Koroteev

- Seventh Guards Army - Shumilov

- 40th Army - Lieutenant General F.F. Zhmachenko

- 53rd Army - Lieutenant General I.M. Managarov

- 3rd Ukrainian Front - Army General Fyodor Tolbukhin

- 5th Shock Army - Berzarin

- 4th Guards Mechanized Corps - Major General V.I. Zhdanov

- 7th Mechanized Corps - Major General F.G. Katkov

- 57th Army - Lieutenant General N.A. Gagen

- 46th Army - Lieutenant General I.T. Shlemin

- 37th Army - Major General M.N. Sharokhin

- 6th Guards Rifle Corps

- 66th Rifle Corps

- Black Sea Fleet

Axis forces

Army Group South Ukraine[18]

- Army Group Dumitrescu

- 3rd Romanian Army

- 6. Armee

- 13. Panzerdivision

- 306. Infanteriedivision

- 76. Infanteriedivision

- Army Group Wohler

- 8. Armee

- 10. Panzergrenadierdivision

- 4th Romanian Army

- 1st Romanian Armoured Division

- 4th Romanian Mountain division

- 8. Armee

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Military planning in the twentieth century", U.S. Air Force History Office

- ↑ United Center for Research and Training in History, Bulgarian historical review, p.7

- ↑ Krivosheev, Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century, ISBN 1-85367-280-7, Greenhill Books, 1997; (chapter on the Jassy-Kishinev operation in Russian)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 http://www.worldwar2.ro/arr/?article=430

- ↑ http://www.militaryphotos.net/forums/archive/index.php/t-17938.html

- ↑ (German)Siebenbürgische Zeitung: "Ein schwarzer Tag für die Deutschen", 22 August 2004

- ↑ John Erickson, The Road to Berlin: Continuing the History of Stalin's War with Germany, pp. 345, 350, 374

- ↑ Major R. McMichael, The Battle of Jassy-Kishinev, (1944), Military Review, July 1985, pp. 52-65

- ↑ A number of less common transliteration variants of the operation's name exists in various historical sources. Among them are Yassy-Kishinev Operation (Chris Bellamy, 1986), Iassi-Kishinev Operation (David Glantz, 1997), Second Iasi-Kishinev Operation (David Glantz, 2007) etc.

- ↑ Dmitriy Loza, James F. Gebhardt, Commanding the Red Army's Sherman Tanks, chapter "A cocktail for the Shermans", p.43

- ↑ Friessner H. "Verratene schlachten." — Hamburg: Holsten Verlag, 1956.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 (Russian)"The Jassy-Kishinev offensive operation, 1944" - an article by Oleg Beginin based on several Soviet history books.

- ↑ "The Romanian 1st Armored Division in August 1944" on axishistory.com

- ↑ (Romanian) Florin Mihai, "Sărbătoarea Armatei Române", Jurnalul Naţional, October 25, 2007

- ↑ George Ciorănescu and Patrick Moore, "Romania's 35th Anniversary of 23 August 1944", Radio Free Europe, RAD Background Report/205, September 25, 1973

- ↑ Andrei Miroiu, "Balancing versus bandwagoning in the Romanian decisions concerning the initiation of military conflict", NATO Studies Center, Bucharest, 2003, pp. 22-23. ISBN 973-86287-7-6

- ↑ (Romanian) "60 de ani de la 'operaţiunea Iaşi - Chişinău'", BBC News, August 24, 2004

- ↑ Friessner H. Verratene schlachten. Appendix 1. — Hamburg: Holsten Verlag, 1956.

Sources

- Art of War Symposium, From the Dnepr to the Vistula: Soviet Offensive Operations - November 1943 - August 1944, A transcript of Proceedings, Center for Land Warfare, US Army War College, 29 April - 3 May 1985, Col. D.M. Glantz ed., Fort Leavewnworth, Kansas, 1992

- House, Jonathan M.; Glantz, David M. (1995). When Titans clashed: how the Red Army stopped Hitler. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0717-X.

- Glantz, David M. (2007). Red Storm Over the Balkans: The Failed Soviet Invasion of Romania, Spring 1944. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700614656.

- Maculenko, Viktor Antonovič; Balcerowiak, Ina (1959) (in german). Die Zerschlagung der Heeresgruppe Südukraine: Aug.-Sept. 1944. Berlin: Verl. d. Ministeriums f. nationale Verteidigung. OCLC 72234885.

- Hoffmann, Dieter (2001). Die Magdeburger Division: zur Geschichte der 13. Infanterie- und 13. Panzer-Division 1935-1945. Hamburg: Mittler. ISBN 3813207463.

- Kissel, Hans (1964) (in german). Die Katastrophe in Rumänien 1944. Darmstadt: Wehr und Wissen Verlagsgesellschaft mbH.. p. 287. OCLC 163808506.

- Ziemke, E.F. Stalingrad to Berlin: The German Defeat in the East, Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army; 1st edition, Washington D.C., 1968

- Dumitru I.S. (1999) (in romanian). "Tancuri în flăcări. Amintiri din cel de-al doilea război mondial." (Tanks in flames. Memories of the Second World War). Bucharest: Nemira. p. 464.

- Roper, Steven D. Romania: The Unfinished Revolution (Postcommunist States and Nations), Routledge; 1 edition, 2000, ISBN 978-90-5823-027-0

External links

- Pat McTaggart, Red Storm in Romania

- Soldiers of the Great War

- (Russian) Jassy-Kishinev Offensive operation (20.08 – 29.08.1944)

- (Russian) Jassy-Kishinev operation, 1944

- (Russian) Jassy-Kishinev operation on Rambler-Pobeda

- Vladimir Tismăneanu, Stalinism for All Seasons: A Political History of Romanian Communism, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2003, p. 86. ISBN 0-520-23747-1

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||